Dubbed the “Sneaker Wars,” Nike’s ongoing lawsuit against online shoe retailer StockX will likely end up dictating how intellectual property law is applied to NFTs. The case, which was filed by Nike in February 2022, alleges that StockX engaged in the unauthorized and infringing use of Nike’s famous marks in its Vault NFT collection.

Who is StockX?

Launched in 2016, StockX is an online resale sneaker retailer. However, its subsidiary business also allows individuals to sell other items – designer clothes, Pokémon trading cards, Playstation 5 consoles, and so on.

As of 2021, the company is valued at over $3.8 billion. And it’s “authenticity guarantee” process sets it apart from its competitors including eBay. As outlined in legal documents, StockX’s proprietary, multi-step authentication process “ensures that items traded on StockX conform to the product descriptions and condition standards advertised by StockX, and that the products offered for sale are what they claim to be, and are not counterfeit, defective, or used.”

When a user buys a pair of shoes off StockX’s website, the seller ships the shoes to one of StockX’s authentication facilities in the U.S. or overseas. For those sneakers that are “verified,” they are subsequently sent to the buyer by StockX, whereas those that fail the authenticity test, according to StockX, are sent back to the seller, removing StockX from liability.

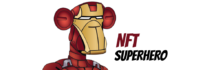

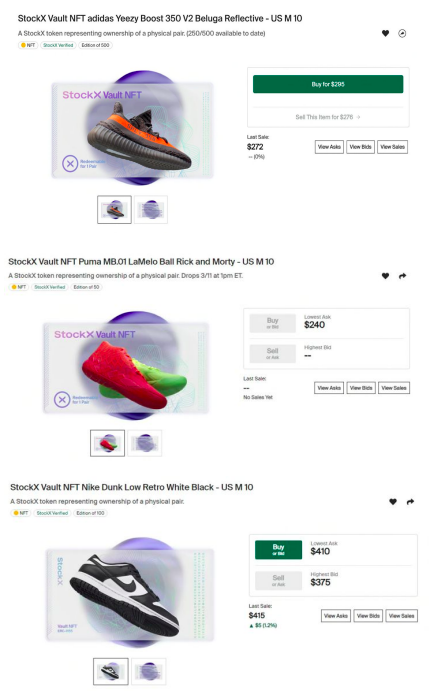

In January 2022, StockX launched its Vault NFT collection, whereby each NFT in the vault is tied to a physical item that StockX sells – in this case, Nike’s Jordan 1 sneaker.

Could Nike be missing the mark?

In its 50-page complaint, Nike specifically alleges that StockX is minting NFTs that use Nike’s trademark, capitalizing off Nike’s goodwill and consequently, misleading customers as to “heavily inflated prices of unsuspecting customers.”

In contrast to the Hermès Int’l v. Rothschild case, this situation seems to differ in that StockX argues that its Vault NFTs are not “virtual products” or “digital sneakers.” Rather, each Vault NFT is tied to a specific physical good that has already been authenticated by StockX, including “styles of shows originally manufactured and sold by Nike, Adidas, and Puma.” It further described its Vault NFT collection as simply the “key” to access the underlying stored item in the vault, with no other form of intrinsic value.

Speaking directly to Nike’s allegations of trademark infringement, StockX argues “fair use” in its March 31 Answer, stating that this is “no different than major e-commerce retailers and marketplaces who use images and descriptions of products to sell physical sneakers and other goods, which consumers see (and are not confused by) every single day.”

The Answer continues to characterize Nike’s Complaint as nothing more than a “baseless and misleading attempt” to interfere with a new technology Nike doesn’t understand, which has opened up a secondary market for the sale of StockX’s sneakers and other goods.

Similar to the rule of law at the heart of Hermès, the Lanham Act and the Second Circuit’s Rogers test also comes into play as legal standards, which set the traditional boundaries of intellectual property and trademark infringement. Under Rogers, the use of a trademark in an artistic work is actionable only if the mark (1) has no “artistic relevance” to the underlying work or (2) explicitly misleads as to the source or content of the work.

Nike files two new claims – counterfeiting and false advertising

Earlier this month, Nike amended its previously filed Complaint, adding two new claims — counterfeiting and false advertising. Since December 2021, Nike says it successfully purchased four pairs of fake Air Jordan 1 Retro High OGs in the black/varsity red-white colorway from StockX’s Vault NFT collection.

In other words, these counterfeit pairs of sneakers were marked as “StockX Verified,” somehow passing the company’s proprietary “authentication guarantee,” which Nike says constitutes false advertising.

Countering Nike’s allegations, StockX stated on its website that the company takes “customer protection extremely seriously,” and these latest claims by Nike are nothing more than a “baseless attempt” to “resuscitate its losing legal case.”

It also said in its statement that Nike’s in-house brand protection team has also praised the company’s authentication program, where “hundreds of Nike employees — including current senior executives — use StockX to buy and sell products.”

What does this mean for NFTs?

The ongoing case tests the relationship between a retailer and manufacturer, bringing up new questions as to the types of NFTs that can be created and how a “fair use” defense could be applied. Until now, it has been rare that our landscape has seen a scenario where a manufacturer brings suit against a retailer for selling products that may have been counterfeited.

The closest comparison to Nike’s ongoing lawsuit against StockX, is the 2011 class-action lawsuit where Coach sued its former employee, Gina Kim, who the company claimed was selling counterfeit Coach bags on eBay (minus the use of NFTs). Another example is the 2004 case where Tiffany sued eBay for trademark infringement in its alleged role in reselling counterfeit Tiffany jewelry (again, without the use of NFTs).

Ultimately, our courts are yet again faced with another opportunity to create a legal precedent for how intellectual property is applied to NFTs.

For more information on this case, please visit Nike, Inc. v. StockX LLC, 1:22-CV-00983-VEC.

Andrew Rossow is an attorney and journalist who focuses on fintech and intellectual property law.

.